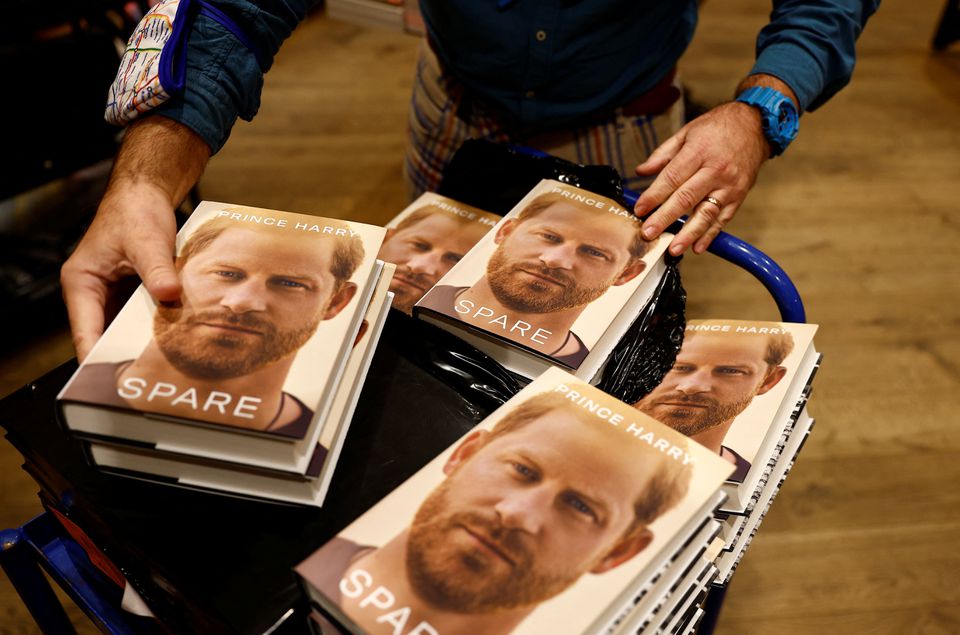

A client recently brought to my attention a New Yorker piece by J.R. Moehringer, the ghostwriter of Prince Harry’s in which he shares his experience collaborating with the prince on his best-selling memoir, Spare.

Though I say with confidence that the books we produce at Oceanside are worthy of any monarch, I haven’t yet had the chance to ghostwrite for a bona fide prince. But I read with great interest Moehringer’s account of the ins and outs, the challenges and the bright moments, of ghostwriting, and I was amused by the commonalities we share in our work even if our clientele is different—from the awkwardness of Zoom interviews, to the creative disagreements that arise between author and ghostwriter, to the fine art of knowing when to push back and when to defer to the author and recognize that while he may not be a professional writer, no one knows his story better than him.

Moehringer writes that Harry initially “wasn’t sure how much he wanted to say in his memoir,” a concern that made Moehringer think twice about accepting the assignment. I often hear the same caveat from prospective clients, and not only memoir clients but writers of business books too. One is hesitant to spill too much about oneself, much less about one’s friends and family. Whatever Harry stated in his book would “would set off a storm,” just be virtue of being a prince in the perpetual spotlight (and a polarizing prince at that.)

But this is no less a valid concern for any “commoner” who pens a memoir—your work might not attract worldwide press scrutiny once it hits the shelves, as did Spare, but it will probably have an impact in your immediate circle. Most authors shy away from engaging with difficult subject matter, especially if it shows people close to them in an unflattering light. There is no easy solution for this, and indeed, some people in your orbit might object to some things you say, or even to the existence of your very book. You must balance the need to tell your story, complete, unabashed, unadulterated, with the equally compelling desire to keep the peace and avoid damaging relationships. (While there is no easy solution, there are certainly measures you can take, such as anonymizing the people you write about. As a ghostwriter, I advise clients how they can navigate this tricky area and write candidly and openly while keeping any fallout to a minimum.)

Evidently, Moerhinger has become a kind of therapist, or at least sympathetic ear, for fellow ghosts: “Some days, the phone doesn’t stop. Ghostwriters in distress. They ask for ten minutes, half an hour. A coffee date,” he writes, listing common grievances: the author can’t remember details of their experience; the author and ghostwriter “despise each other”; the author doesn’t return calls.

I beg to differ. The first problem is an impediment but hardly a problem—as a ghostwriter, I’ve learned to coax details, sometimes long-forgotten, from clients, and to use the magic of storytelling to fill gaps and the craft of writing to stitch together fragments into a cohesive whole. I’ve never worked with a client I disliked, much less despised, and I like to think they’d say the same of me. This situation doesn’t happen because it can be avoided before you ink a deal. In truth, if your client despises you, and vice versa, you are probably doing something wrong.

As for being “ghosted,” well, that comes with the territory. A good ghostwriter excels not only at research, writing, and editing but project management as well. Sometimes clients need boundary-setting and the imposition of deadlines to make sure they stay on top of their own project.

As a ghostwriter, I infrequently talk to colleagues—we are few in number and tend to be the reclusive sort (it’s in the name, after all!) So I enjoyed Moehringer’s candid insight into his work.

And hey, Prince William, if you don’t want to be literarily one-upped by your younger brother, hit me up.

Recent Comments